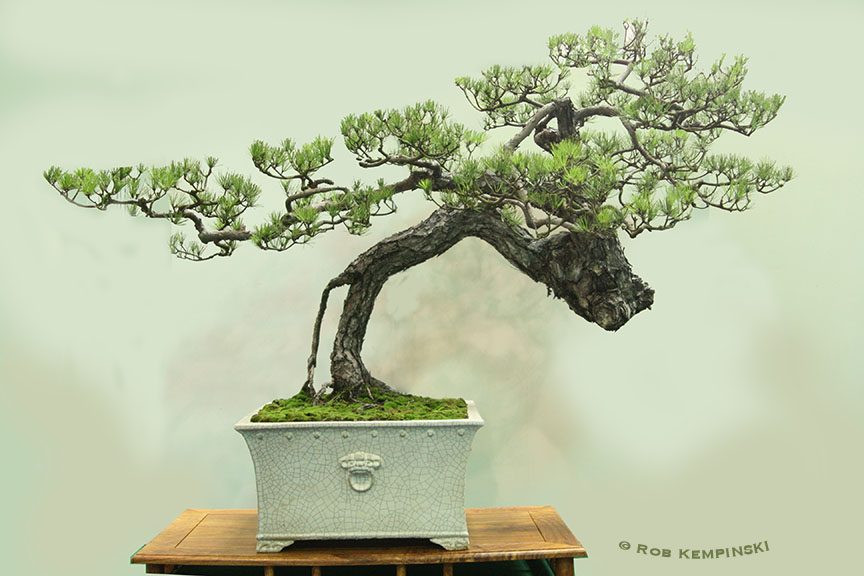

You know the cure of the helmet on a stick has been out there for centuries, just most of us don’t know about it. I first encountered the cure when I visited some Chinese bonsai shows, especially in southern China near Guangzhou. There I noticed the artists had cut off most of the ramification of their bonsai trees (well to be precise I should say penjing as that is the Chinese word for bonsai trees.) It seems the Chinese artists had totally eschewed the triangular form. Many even went beyond and did not have a traditional domed canopy. Horrors you say. How could that be? Branch ramification is the hallmark of bonsai design. It shows age and attention to detail. Yet the Chinese bonsai I saw had all that plus more. Let’s examine how the cure happened.

The cure is Lingnan penjing. Lingnan penjing comes from the Lingnan region of south China near Guangzhou (old Canton) and its surrounding towns. There artist styling penjing strove to reflect several key Chinese artistic sensibilities: those of openness, nature and refinement. This school of thought applied to trees dates back to the 15th century.

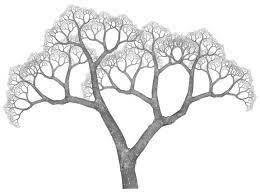

Fractal mathematics tree form

A hallmark of the technique is openness. To make an open tree the artist merely lets the tree grow, then cuts it back hard. The Chinese call it “Xu Zhi Jie Gan”. In English we say “Clip and grow”. The concept is utterly simple – let a branch grow for a season then cut it back hard. The buds that form then grow for season or two and once again are cut back hard. The ensuring pattern will have an airiness to it with a reticulated form very common in nature. Some of the patterns are reminiscent of fractal derived patterns. Yet to make the natural form the artists are totally artificial. (Remember back in August’s Kempinski Korner I said there is nothing natural about bonsai). Using only scissors the artist chops the branches. The tree uses its genetics and processes to respond with new growth.

Another technique to espouse openness is the defoliation of the tree for display and or just personal enjoyment. With all the leaves removed the full near randomn morphology of the design becomes apparent. While many artists use defoliation to grow smaller leaves, in Lingnan styling, the goal is not the leaves but to reveal the structure. Living in south China the trees can tolerate the regular defoliation regime whereas up north, trees wouldn’t appreciate monthly nudity.

Refinement reflects the continued application of this process to get progressively finer shapes. And if left to the trees genetic programming the ensuing pattern of branches has none of the traits of a poodle-styled helmet on a stick. In doing so the artist pretty much ignores the bonsai rules frequently taught to Japanese adherents. Yet the technique is not instant bonsai. It can take years for the true Lingnan form to develop.

Most in the west look to Japan for bonsai inspiration and hence our trees have the typical triangular crown on a trunk, the dreaded helmet on stick, but there is a whole lot out there for those interested in broadening their horizons. In September the club was exposed to Laurent Darrieux’s Cosmic style. I suggest one go beyond that and examine the Lingnan style and give it a try.